As a professional circus performer, Eve Timmins is no stranger to taking big risks in the air. She’s also no stranger to crash landing.

“There’s a scary moment when you know everything’s gone wrong and you can feel yourself falling,” says Timmins, “but you don’t know how bad the landing’s going to be.”

But in August, she was set to soar to new heights. Collective Circus — the company Timmins co-founded with several other performers — had been granted the opportunity of a lifetime.

For two weeks, the Brisbane-based performers would train in the world-class Albury facilities of the Flying Fruit Fly Circus, developing a show they’d tour nationally later this year.

Only one obstacle stood in their way.

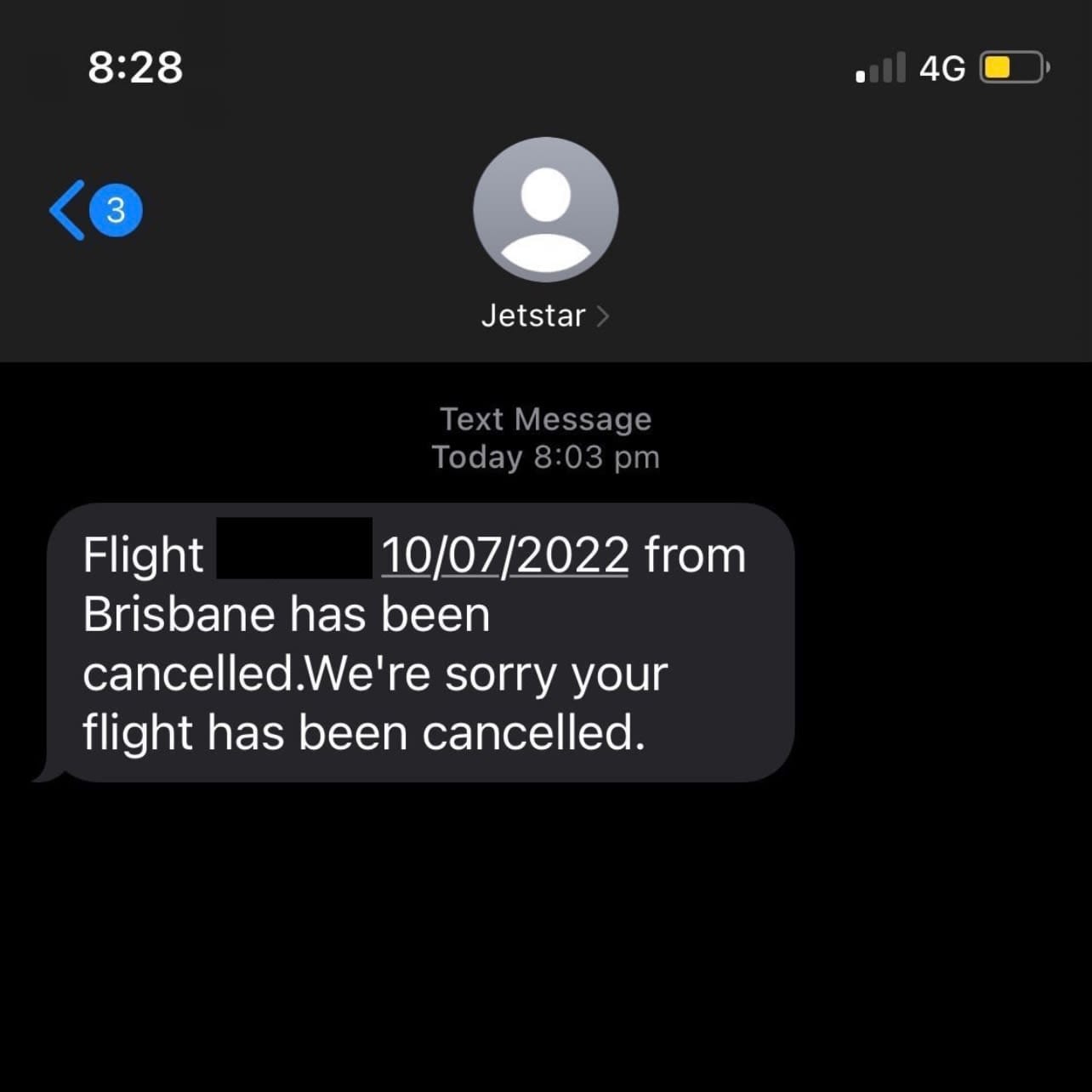

“Jetstar dropped me worse than any acro partner ever has,” Timmins remembers.

When the airline texted her just before departure with bad news, Timmins became one of many travellers swept up in a record rate of flight cancellations.

The industry’s ‘On Time Performance’ — a group of metrics recorded by the Bureau of Infrastructure and Transport Research Economics (BITRE) — was the “worst ever” in June this year.

But with Covid restrictions lifted and people champing at the bit to travel, one would have expected 2022 to be a year of success for airlines. So, what happened?

Personalise this story: Country kid or city slicker? Press the classifications in the legend to isolate your own region.

This chart shows every passenger flight operated in Australia since 1985. The data comes from BITRE, a Federal Government agency which tracks a range of aviation industry statistics.

Here, we can see strong growth in flight activity being reversed by the pandemic. Covid impacts saw this slump to levels not seen since the "recession we had to have" of the early 90s.

The Covid Crash

Before the pandemic, years of strong growth saw industry activity peak at nearly 61 million domestic passenger flights operated in the 2018-19 financial year.

But the onset of the Covid pandemic saw two thirds of flights vanish into thin air, with airlines operating just 20 million flights during the 2020-21 financial year.

That was a shock for Australia's broader travel industry, which accounted for 600 thousand jobs in March 2020. Three months into the pandemic, the Australian Bureau of Statistics reported 100 thousand jobs were gone.

Cassandra Tayler saw her job at a leading travel agency become "collateral damage" in 2020. At the time, she'd been a travel agent for 14 years.

"I'd always been interested in other countries," says Tayler, who took her family on a three-month round-the-world trip before entering the industry.

She spent 18 months researching and booking countless hotels and connecting flights. Then, when the time came for the trip, "everything just ran perfectly".

Tayler says her friends were impressed by the level of coordination, and suggested she become a travel agent. She got her first placement while studying.

"For the people that come up in the travel industry - if you're really into it - it's a real passionate industry," says Tayler. "It was such a colourful industry to be in."

That passion has followed Tayler to her current work. After starting in an admin role at a construction company, Tayler now also coordinates the firm’s travel through her own agency, Tayler Made Travel.

But as she settled in at the new company, the travel industry continued cutting back. Airlines cancelled 7,843 flights in March 2020, a record-high at the time.

Another 2,283 flights failed to take off the next month. But by May, airlines cancelled just 28 flights, ending a rapid industry downsizing and heralding a new normal.

Personalise this story: Mouse over the graph to see how your city - and your preferred airline - stack up against the competition.

You've seen how much the industry contracted, but how many flights were cancelled to get there? This graph compares the decade of BITRE data before the pandemic with the aftermath.

You can switch between seeing the cancellations in capital cities and by major airlines. The numbers between graphs won't add up because airlines fly to more than just capital cities.

Cancellations Unpacked

Throughout this story, you’ve seen lots of data from BITRE. So it’s worth taking a moment to understand what the agency does, and what the numbers it collects really mean.

BITRE is a government agency established in 1970 to report on Australian transport - including flights, rail, road use and more. BITRE says its data has "informed decisions by governments and industry".

But 2020's fall in aviation activity wreaked havoc on BITRE's data-quality safeguards. This meant the agency had to change the way they reported on the industry.

BITRE's been collecting “on-time performance” statistics since 2003, monitoring how often flights arrive and depart on time - and how many flights are cancelled altogether.

But it only publishes data on qualifying flight routes. Normally, a route (for example, Canberra to Cairns) must average at least 8,000 passengers a month. This is over a six-month period across all flights and airlines.

However, when the sector tanked during the pandemic, many routes no longer met this requirement, so BITRE dropped it. From March 2020, a route only needs two competing operators (say, Qantas and Virgin) to qualify.

That means an airline like Rex escapes a certain amount of scrutiny. It’s the sole operator on many regional routes, including its famous “milk-run” route through country Queensland, so there's no data for these flights.

Lowering the bar to (database) entry also introduces more volatility into the dataset. Data on smaller routes which may have been unreliable for years before the pandemic may not have been published until recently.

So, with those limitations in mind, perhaps it's worth taking a quick look at the industry from another angle.

Personalise this story: Before starting the animation, press the name of your preferred airline on the right of the chart.

Here's some Google Trends data over the same 12-year period as BITRE's cancellation data. This graph shows how many people searched for an airline's contact details, which may indicate how many issues arose.

You can switch between the percentage data - compared against the 2020 peak of searches for "contact qantas" - and a comparative ranking of each airline. Make sure to select 'All Airlines' before viewing the ranking.

Searching for Support

When Eve Timmins received that fateful late-night text from Jetstar, she had to Google what to do next. The text didn't include how to contact the airline, or what Timmins' recourse could be.

Google gave her the number to Jetstar's support hotline, which Timmins rang right away. Unfortunately, every other passenger on her flight appeared to have the same idea.

Over the hour Timmins spent on hold before giving up, she "stress ate" an entire block of cheese. The exercise established she would not make it to Melbourne.

The next available flight on Jetstar's website offered Timmins took off two days later, meaning she'd miss her connecting V/Line train and several days of training.

That wasn't an option. Timmins ended up booking a direct flight to Albury with Jetstar's parent company Qantas - at a steep premium for booking last minute.

The new flight cost $560, a far cry from the $130 deal Timmins scored originally. Jetstar only compensated the original ticket, leaving Timmins $472 out of pocket when including the missed V/Line train.

That's par for the course with cancelled flights. The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission says airlines "do not guarantee flight times, and flight times do not form part of their contract of carriage with you".

But Cassandra Tayler has two tips for easing the pain. Taking out insurance can help travellers claw more money back, and engaging a travel agent can make resolving the situation their job instead of yours.

Personalise this story: Before starting the animation, press the name of the city where you live on the right of the chart.

This chart shows the last ten years of BITRE cancellation data for each capital city. It shows the most unreliable cities for passengers to depart from over time.

You can switch between viewing the percentage data and a comparative ranking of how each city performed over time. Make sure to select 'All Cities' before viewing the ranking.

City Impacts

Let's look at how many flights were cancelled in the average month in each capital city - both in the decade before and two years since. Cities are ranked by their current cancellation rate.

Capital City | Pre-Covid | Post-Covid | Ranking |

|---|---|---|---|

Melbourne | 2.15% | 13.19% | Worst |

Sydney | 2.32% | 11.12% | 7th |

Canberra | 2.70% | 9.93% | 6th |

Adelaide | 1.09% | 8.84% | 5th |

Brisbane | 1.58% | 8.12% | 4th |

Hobart | 0.96% | 7.52% | 3rd |

Perth | 1.29% | 6.51% | 2nd |

Darwin | 0.73% | 4.43% | Best |

Melbourne spent the most days in lockdown, and had the most separate lockdown periods, so is unsurprisingly the least reliable city to depart from since the pandemic began.

Surprisingly, Canberra is overrepresented in cancellation statistics. That's despite spending relatively few days in lockdown and having a small population. It's also not a new phenomena.

There's no love lost between Canberra Airport and 'Australia's national carrier' Qantas, with the two entities locked in a bitter feud back in 2018.

That March, Canberra Airport managing director Stephen Byron spoke out about "very high and concerning cancellation rates by Qantas" in the Canberra Times.

Qantas hit back that May, with boss Alan Joyce telling industry: "Maybe the airport should be called ‘The Canberra Pirates’ because you wouldn’t have this in Somalia."

Four years on, it appears the situation hasn't improved, with nearly one in ten flights scheduled to leave Canberra not making it off the ground since the onset of the pandemic.

Overall, it turns out Eve Timmins' experience wasn't a given, but also not entirely unexpected, with Brisbane Airport right in the middle of the current city ranking. But airports are only half the story; let's turn the focus back on airlines.

Personalise this story: Before starting the animation, press the name of your preferred airline on the right of the chart.

This chart shows the last ten years of BITRE cancellation data for each of the big four airlines: Qantas, Virgin, Jetstar and Rex. Qantas' and Virgin's regional subsidiaries are also counted toward their totals.

You can switch between viewing the percentage data and a comparative ranking of how each airline performed over time. Make sure to select 'All Airlines' before viewing the ranking.

Ranking the Airlines

It's clear the title of Australia's most unreliable airline is one hard fought for, with Qantas, Virgin and Jetstar all tussling for the top spot over the last decade.

Airline | Pre-Covid | Post-Covid | Ranking |

|---|---|---|---|

Jetstar | 1.76% | 10.55% | Worst |

Virgin | 1.73% | 8.79% | 3rd |

Qantas | 1.88% | 8.08% | 2nd |

Rex | 0.67% | 3.61% | Best |

The data confirms Timmins' experience of Jetstar being Australia's most unreliable airline. But what it doesn't confirm is the widely-held perception of Qantas going down the toilet.

In fact, it turns out Qantas was Australia's most unreliable airline... but only before the pandemic. Since then, while its reliability has taken a hit, it's still out ahead of main competitor Virgin.

Perhaps the unique scrutiny Qantas attracts is a consequence of its own marketing. Despite being privatised over 25 years ago, the airline still calls itself 'Australia's national carrier.'

As Andrew Curran writes for Simple Flying: "Australian's [sic] have willingly adopted it into their national consciousness for a century. And Qantas has astutely utilised this."

But overall, Australia's biggest three airlines have a similar 8 to 11 per cent cancellation rate, signalling the problems afflicting Australian aviation aren't unique to one particular carrier.

Cassandra Tayler attributes many of the industry's issues to growing pains after its dramatic downsizing. The number of travel industry jobs still hasn't returned to pre-Covid levels.

"A lot of it has been staffing. They don't have the baggage handlers; they don't have the check-in staff," she says. "People looked for another job, got into a different industry and haven't come back."

Tayler also says assets are an issue. Rental car companies which sold off fleets have now been hit by a global computer chip shortage, and airlines themselves have had to prepare their planes.

"It's not a matter of just, you know, putting a plane in the sky and off we go again," she explains. "It takes a while to prepare a plane that's been in the desert for two years to be up in the sky again."

After a challenging couple of years, there may be good news for domestic travellers. In August, cancellations were down to 3.2 per cent - getting closer to the 1.9 per cent average of last decade.

Cassandra Tayler has been optimistic since re-entering the industry with her own travel agency. She says late 2023 could be the industry's fresh start, led by package holidays.

"People will still be apprehensive," she says, "but I'm expecting come mid-January next year, people will start booking for the end of next year. I've already got bookings for coach tours and cruises."

Eve Timmins is one of those apprehensive travellers, planning an overseas holiday for the middle of next year. It's still early days, but she knows who she won't be booking with.

“In circus, you have to have absolute trust in your partner,” she says. “Jetstar has lost my trust.”