with Natalie Heslop and Nyah Barnes

Locals in Melbourne’s west are facing a “significant geographic disparity” in psychiatry wait times and costs, Medicare claims data has revealed.

A growing number of community-based services are starting to support Victorian patients and their families outside of the Medicare system.

Politicians across the aisle are calling for more action, while a health inequality researcher says any response should involve the whole government.

Mental health worker Natasa Adamovic says her commute to the west is well worth the drive from the other side of the Yarra.

She’s been running Lifeline’s crisis call centre at Victoria University’s St Albans campus since the organisations joined forces in 2023.

“It was just a great opportunity for us to partner with Victoria University and be on campus,” Ms Adamovic said.

“We can be seen, and students have easy access to us as well, and also just be a part of the Western Melbourne community.”

On the other end of the phone line, the call centre provides psychology students with hands-on experience while making a real-world difference.

Students yet to finish their Honours study can otherwise find it difficult to secure work or placements in the mental health sector, where the federal government has found a 32 per cent worker shortfall.

All volunteers — students or not — are encouraged to visit the centre at least once a fortnight, where they get more than one year of training and ongoing supervision after that.

Ms Adamovic says volunteering lets the students grow their practical skills.

“There’s a lot of opportunities for growth,” she says, “not only just coming and doing volunteering, but also being a part of the organisation and working and growing with the organisation, which is really fulfilling.”

Data in detail

Lifeline says it moved into St Albans after calls from Melbourne’s north and west rose by more than a third.

We’ve investigated mental health in the west by speaking to researchers who’ve been tracking measures such as rates of mental distress, and how long people are waiting to see a psychiatrist.

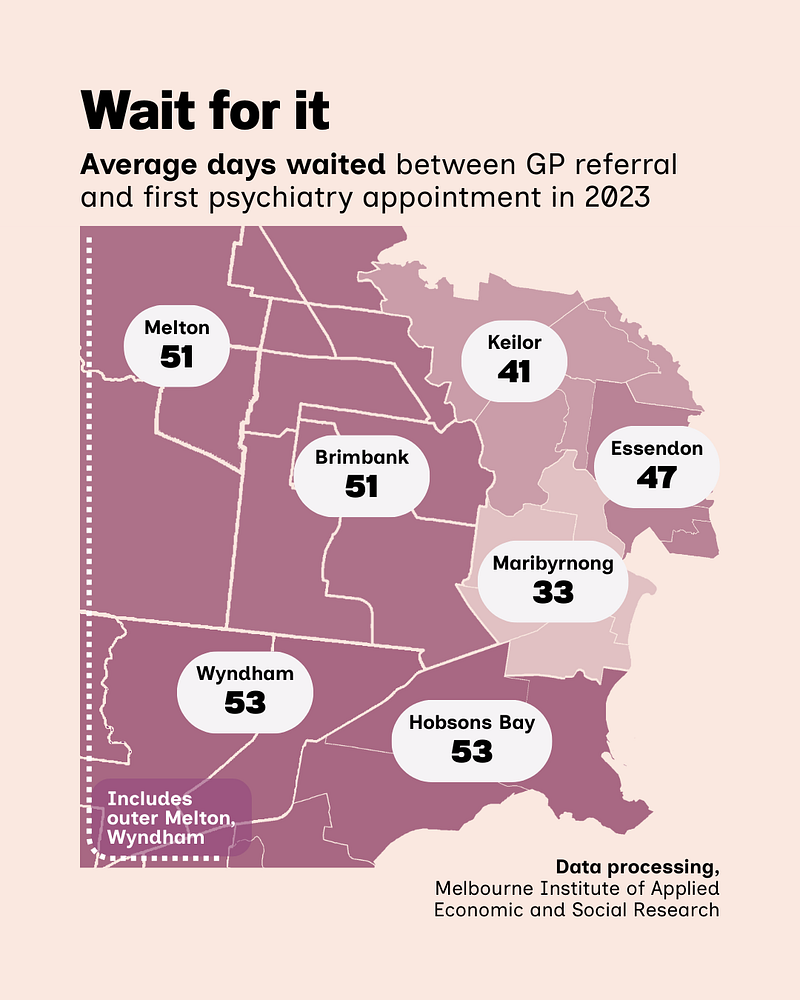

Average waits of more than seven weeks after getting a GP referral feature across most of Melbourne’s west, including in places like Brimbank and Melton.

The University of Melbourne’s Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research has found Maribyrnong locals waited the shortest time: just 33 days or five weeks in 2023.

But the delay stretched as high as 53 days on average in Wyndham and Hobsons Bay.

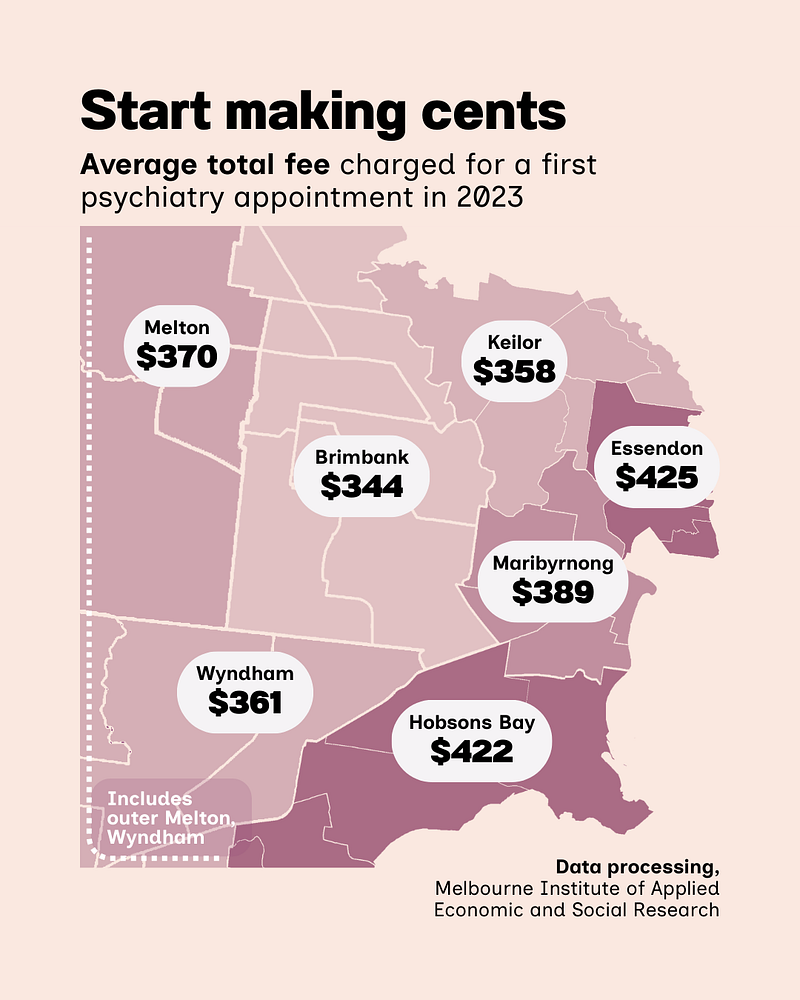

Research fellow Dr Ou Yang says the institute’s analysis of Medicare psychiatry claims shows a “significant geographic disparity” in fees as well.

He explains that’s partly caused by the “concentration of the specialists in the city, so there’s very little supply for the patients in the outer suburbs”.

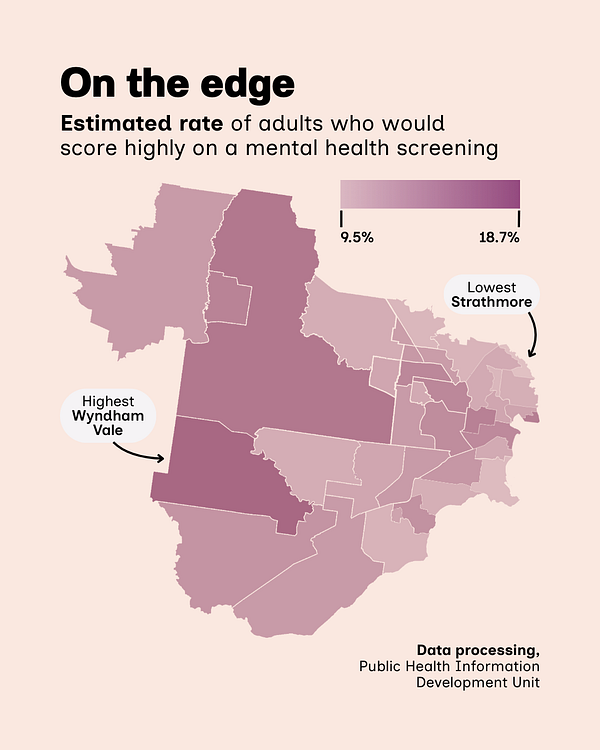

The delay cuts especially deep in places like Wyndham Vale, estimated to have the west’s highest rate of mental distress in modelling released by the Public Health Information Development Unit (PHIDU).

There, 18.7 per cent of locals would score highly on a standard psychological distress screener, the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale.

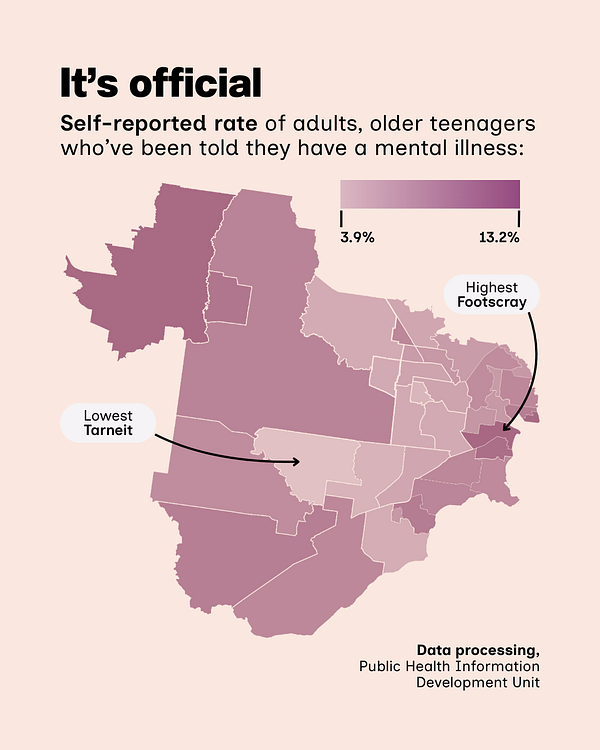

But a different approach raises concerns in Footscray, where 13.2 per cent of locals reported on the 2021 Census that a doctor or nurse said they have a mental health condition.

Measures of mental distress show varying rates across the west, with peaks in both outer areas and closer to the CBD.

PHIDU director Dr John Glover has spent decades mapping how socioeconomic disadvantage connects to public health outcomes and says self-reported mental health data shouldn’t be dismissed.

He explains that both the estimates and self-reports help to create a picture of distress in the west, creating maps with an almost “street-by-street” level of detail.

“But I think what we see across western Melbourne is similar,” Dr Glover says, “poor education and unemployment”.

“The further out you go,” he explains, “it just gets more and more difficult with the stress of travel time and all those other stresses that come with living away.”

Estimates of distress outstrip reports of diagnoses in almost every part of the west, despite the Census question casting a wider net by also covering conditions that don’t cause distress.

Tarneit is among the places facing the longest average psychiatry wait, and reports the lowest diagnosis rate at just 3.9 per cent–the largest gap between self-reports and estimated distress.

Costs for a first psychiatry appointment also varied across the west in 2023, with Brimbank enjoying the lowest average cost of $344, while the average in neighbouring Hobsons Bay climbed $78 to a total of $422.

The Melbourne Institute claims analysis averaged total charges inclusive of rebates, and finds Essendon locals faced the highest average fee at $425.

We raised these fees with the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists; it told us it “does not set or provide information on the fees for psychiatrists seeing patients, as psychiatrists set their own private fees”.

“We’ve consistently advocated for removing barriers to specialist mental health support for people across Australia, including those in outer suburban, regional and remote areas, and ensuring equitable access to quality mental health care for everyone, regardless of postcode,” a spokesperson said.

Growing support

When taking a call from someone in crisis, Lifeline’s local volunteers may opt to refer them to more help in the community, such as the state government’s growing network of Mental Health and Wellbeing Locals.

A Premier’s office spokesperson says the centres have been a “key recommendation of the Royal Commission into Victoria’s Mental Health System” and are designed to help adults experiencing mental illness or psychological distress.

The Locals are a 15-location network of walk-in mental health centres across the state, offering clinical therapy and treatment as well as education and peer support groups.

“Support is free and a GP referral or Medicare card is not required,” the spokesperson says. “These centres bridge the gap for those who need more than a GP can offer, but don’t meet the threshold for hospital care.”

Dr Sarah Mansfield is the Victorian Greens’ mental health spokesperson and ran for Victoria’s upper house, representing the state’s west, after growing frustrated with challenges she says her patients faced.

“It’s been incredibly frustrating not being able to access the kind of care that my patients have needed,” the deputy Greens leader says. “Even with things like what is known as a GP mental health care plan … there’s still typically an out-of-pocket cost, and then you’ve got to be able to find a provider.”

WATCH: Loughlin Patrick speaks to Channel 31's Newsline about the investigation

The Locals are also supposed to help people coordinate their care with other providers, but Dr Mansfield cautions that “some of those connections between different parts of the sector haven’t necessarily been occurring as smoothly as they could”.

Each Local is state government-funded, but run by partner organisations with differing processes and policies; Cohealth declined our request for comment about its Sunshine centre covering Melbourne’s metro west.

“It’s not to say that they’re not working hard and they’re not doing a good job,” Dr Mansfield says, “but I think there’s still a lot of work to go into in terms of figuring out the optimal model.”

Coalition mental health spokesperson Emma Kealy MP wasn’t available for comment, but has told state parliament that “we have seen in this year’s budget that all of the budgets have been cut for the future rollout of Mental Health Locals.”

“The mental health sector is very, very concerned about this because it is having an impact on the ability to recruit people,” Ms Kealy said on National Suicide Awareness Day in September, adding, “there is great uncertainty around this”.

Mental Health Minister Ingrid Stitt didn’t reply to our questions by the deadline, but the premier’s office has told us the state government intends to launch seven more Locals in communities such as Wyndham.

“Victoria continues to lead the way for mental health reform nationally,” the spokesperson said, “with more than $6 billion invested in the system over the past three years–the largest investment in mental health of any state in Australia.”

- We collected public health data and interviewed the researchers who published it.

- We contacted spokespeople from the state government, the Coalition and the Greens.

- We visited community-based mental health services in St Albans, Sunshine and Brimbank.

- When people couldn’t or wouldn’t comment, we used their existing public statements.

While Locals aim to directly support people who have a mental illness, a sister Mental Health and Wellbeing Connect program focuses on families and carers who can be left in the shadows.

Jesuit Social Services runs a Connect centre in Brimbank that covers Melbourne’s metro west, with centre manager Nick Pace says its team is dedicated to “supporting really vulnerable members in the community”.

“Prior to this,” Mr Pace explains, “there hasn’t been any specific supports that are tailored and nuanced to provide support to people who look after someone with a mental health or substance use issue.”

The centre offers counselling, practical guidance on systems like Centrelink and the NDIS, and group programs to let carers “know that they’re not alone and to share their experiences”.

Mr Pace draws on both professional and lived experience to lead a team of practitioners–many with family experience themselves–in supporting people at the centre, in the community and in their homes.

“People can drop in and walk into our service, they can give us a phone call, they can email us, it’s really easy and accessible,” Mr Pace says.

For some, it’s a rare opportunity for respite and connection in lives marked by stress and exhaustion.

“Caring for someone with mental health and substance use issues takes a lot of resources,” explains Mr Pace. “People who are accessing this service they’re often tired, they’re overwhelmed, they can be really burnt out.”

By offering “a safe and warm and welcoming space” that validates their experience, the service aims to break down stigma, foster resilience, and ultimately improve recovery outcomes for entire families.

What’s next

The state government is continuing to grapple with rising psychiatry wait times and fees, an issue in the making since before its mental health royal commission handed down its findings.

Melbourne Institute researcher Dr Ou Yang says telehealth hasn’t been having the expected effect, despite being “a boon for the patients in the rural areas and the outer suburbs” who have needed to travel less.

“It takes the specialist the same amount of time to run a telehealth consultation as an in-person consultation,” he explains. “The capacity with specialists is fixed, it’s highly constrained.”

Victoria’s 15-centre Local network will add seven satellite centres by the end of this year, offering a reduced service run by staff from existing centres.

The Victorian Greens have welcomed that continued investment.

“We need a lot more of them,” Dr Mansfield says, “and much more investment in building up our mental health care workforce.”

The upper house member says the state needs more “young people moving into the mental health care space”, system-wide reform and integration to truly close the gaps for the next generation.

PHIDU director Dr Glover is more blunt in his assessment of how governments should act on health inequality.

“The most disadvantaged areas, their death rate is twice that of the most well off,” Dr Glover says. “It’s really disgusting, it’s terrible, and we’re not really addressing it.”

He remains frustrated that, despite the data, little action is taken.

“We just haven’t coordinated to do anything about it,” says Dr Glover. “We’ve got a lot of good things going on in Australia, but I think we could do a lot better in this area”.

Nyah Barnes, Natalie Heslop and Loughlin Patrick contributed to this report.

You can call Beyond Blue on 1300 22 4636 or Lifeline on 13 11 14.

In a life-threatening situation, always call Emergency Triple-Zero (000).